ADRIAN — Melissa Archer was already a mother of four, the youngest of whom was a freshman in high school, when a new baby came into her and her husband David’s life.

The couple named their new arrival Jasmynn, and “I was madly in love with everything about her,” Melissa said.

It wasn’t long, however, before the couple realized something was different about their little girl. At first, Melissa chalked it up to just not remembering what babies were like, since it had been so long since her last child was born. But when Jasmynn got a little older, she started exhibiting behaviors like spinning around and hiding behind the furniture.

And even though Melissa was a teacher for the Lenawee Intermediate School District and saw other children like Jasmynn in her building all the time, when it came to her own child “I just didn’t see it,” she said.

The “it” was that Jasmynn was autistic. She was diagnosed at about age 3 ½ after the Archers took her to the University of Michigan Medical Center to be evaluated.

“It was like a bomb went off,” Melissa said. “I was shell-shocked.”

So was David. “I was devastated,” he said. “But my attitude was, she is who she is and she’s the way God made her.” And, of course, the couple knew they would not love their youngest daughter any less.

Melissa, being a teacher, started educating herself on autism, and the Archers were able to get Jasmynn enrolled in the LISD’s program for children like her. “The ISD was phenomenal,” Melissa said.

Jasmynn was non-verbal until age 5. And then, one day, she came home from school and not only started singing the “Alphabet Song,” but could put a set of letter magnets on the refrigerator into correct order.

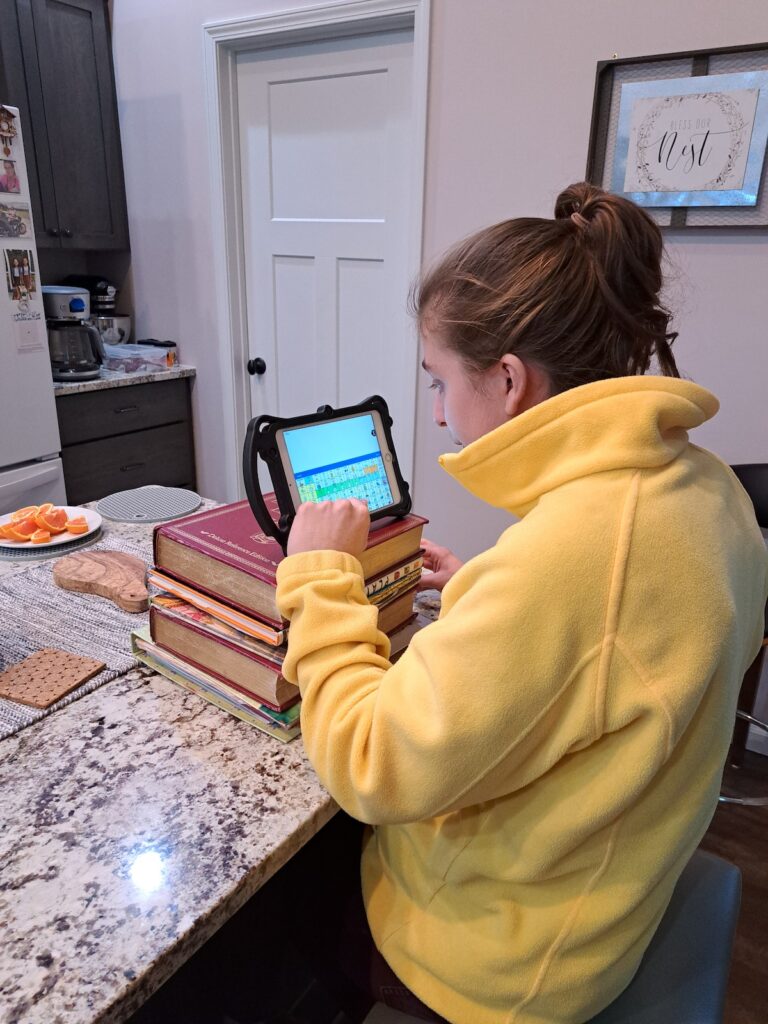

A big breakthrough came when she was given an iPod Touch that was pre-loaded with a communication app. Melissa remembers the moment that they went to the grocery store and when they got to the produce section Jasmynn knew what a rambutan was — because it was pictured in the app she had.

“That was when we knew she was very smart and just couldn’t show the world that,” she said.

As iPods gave way in the world of technology to iPads, even more of the world opened up for Jasmynn. And that led the Archers, in 2012, to form Jasmynn’s Voice, a 501(c)3 nonprofit that gives iPads loaded with assistive-technology apps to others like her.

At first, the organization only operated in Lenawee and Washtenaw counties. Later, Branch, Calhoun, Clinton, Eaton, Genesee, Hillsdale, Ingham, Jackson, Lapeer, Livingston, Macomb, Monroe, Oakland, Shiawassee, St. Clair, and Wayne counties were added.

To date, Jasmynn’s Voice has given more than 700 iPads and communication apps to individuals with autism in those counties and taught their families how to use them. The organization has raised just over $750,000 for the cause since its start.

Much of that funding has come from small donors and community groups. The organization also holds fundraisers such as the annual “Tee 4 Technology” golf outing held every September.

“The community has always been very good to us,” Melissa said.

How do people with autism benefit from having these iPads?

Melissa gave the example of a parent being able to show an autistic child pictures of different kinds of crackers so the child can choose which kind he or she wants. “It’s so wants and needs can get met,” she said.

For the child, “it lessens the behaviors of frustration from not being able to communicate.”

The technology also allows these children “to show you what they can do,” and for Jasmynn, it’s a way to get out all the things that are inside her mind that she can’t verbalize.

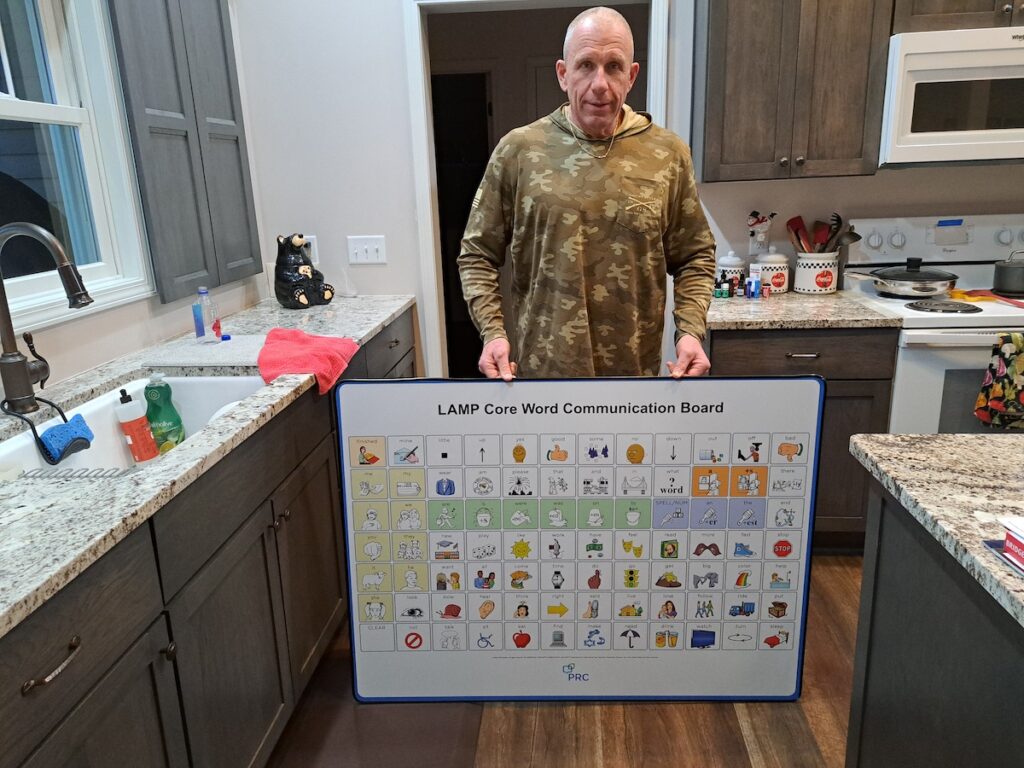

A related aspect of the organization’s effort to help those with autism communicate can be seen at area playgrounds: the installation of what are called “core boards,” depicting a series of icons that help people with autism indicate what they want.

The next iPad gifting event — the organization’s 33rd, since they do it in April and October — takes place April 6 at Adrian College. April is Autism Awareness Month, and Melissa and Jasmynn use that month to go into classrooms and make educational presentations.

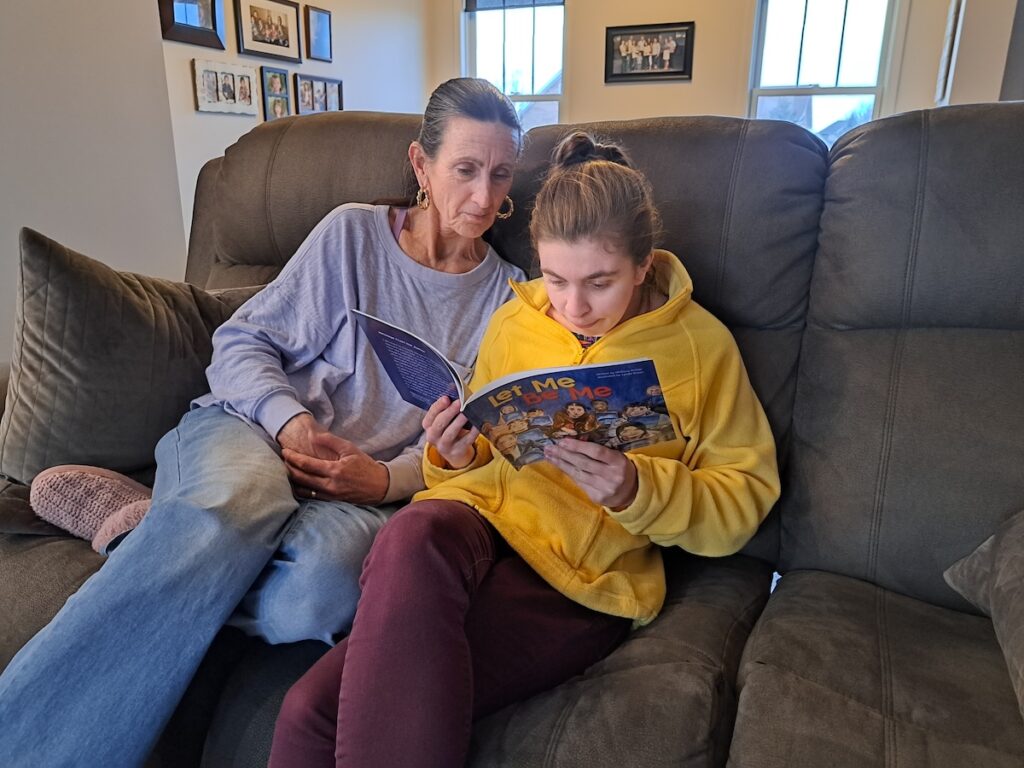

The pair does a slide show and reads a book. And now, they have their own book to read: “Let Me Be Me,” a children’s story which Melissa wrote, with her daughter Lynde Bryan doing the illustrations, to help other people understand how children like Jasmynn see the world.

A book launch will take place at 1:30 p.m. Sunday, April 27, at NewLife Church, located in the former Elder-Beerman space at the Adrian Mall.

The church also hosted a Tim Tebow Foundation “Night to Shine” event for people with special needs in February, and Jasmynn’s Voice donated funds to establish a room at the church for people who have sensory issues and need a space they can go to that’s calming and quiet.

“It’s lovely, and Jasmynn thinks she owns the room,” Melissa said, laughing.

The Archers’ autism-awareness outreach also extends to working with law enforcement. David, a detective sergeant in Milan, has for many years offered training geared toward helping police officers interact with people on the autism spectrum.

“People misconstrue,” he said, and might think a person is on drugs or is having a mental-health issue when the person is actually autistic. And children with autism may run away, leading police to get involved in searching for them.

“I tell parents to get to know their local law enforcement,” David said.

Jasmynn is now 24 years old. She loves music, enjoys going to church, and goes places with the family all the time.

“She has a large following of people who love her, and she’s a happy girl,” David said. And over the 12 years since the foundation named after her was formed, “she’s helped a lot of kids.”

For more information on Jasmynn’s Voice, go to jasmynnsvoice.org or the organization’s Facebook page, facebook.com/jasmynnsvoice.