For Kimberley Davis, the fight against sickle cell anemia is personal.

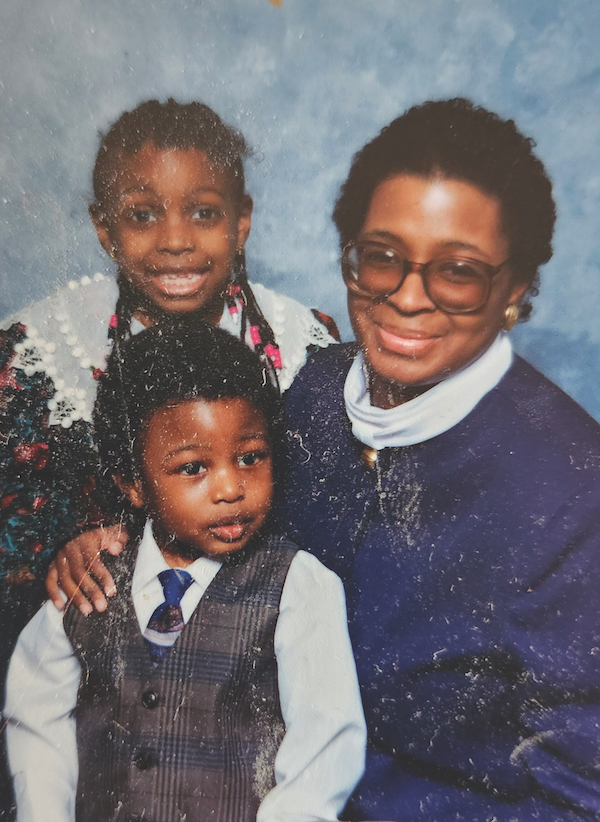

After seeing the effects firsthand, Davis lost two children to sickle cell disease: a daughter, Mariama Walters, who died in 2007 at age 21, and a son, John Amara Walters, in 2021 at age 29. But out of this devastating loss an advocacy group — KMD Advocacy Center — was born.

Sickle cell anemia is one of the most prominent life-threatening illnesses — more prevalent than cystic fibrosis or hemophilia — but Davis said research and treatment are woefully underfunded.

“My goal is making sure the awareness is there,” Davis, a former assistant professor at Adrian College, said. “Once people are more aware of what sickle cell is, what the numbers are, they’ll listen. That’s the key, getting people to listen.”

Sickle cell disease affects red blood cells, taking them from their typical round, flexible structure and shaping them into a more rigid sickle or crescent form. This shape and rigid structure makes the cells become sticky, which can cause pain and block blood flow. These cells also die much sooner than typical red blood cells, leaving people with the disease with a shortage of oxygen-providing red blood cells. It can also cause episodes of extreme pain when blood flow is blocked, swelling of hands and feet, frequent infections as a result of damage to the spleen, delayed growth or puberty, and vision problems.

Complications from sickle cell disease can be fatal but the illness is broadly misunderstood and underrepresented, Davis said, and KMD is working to correct that.

The advocacy center was at least partially inspired by Davis’ son and his work on Capitol Hill, where he was a legislative aide to Sen. Chris Van Hollen (D-Maryland). Davis and the center’s work is rooted in policy change and driving additional research and funding toward fighting the disease that claimed her children’s lives.

“I wanted to do something to honor them,” Davis said.

As one of the first steps, the center worked alongside Van Hollen to create the Sickle Cell Care Expansion Act, legislation that was designed to strengthen the medical workforce that treats sickle cell disease and strengthen services available to those living with the disease.

“For Americans living with sickle cell, access to their doctors and treatments can be one of the biggest challenges they face,” Van Hollen said on his website. “And while medical advancements over the years have enabled these Americans to live longer, the supply of care simply hasn’t kept pace with demand. This bill will help close this gap by increasing the size and capacity of the medical workforce that is trained to treat sickle cell. Better care is out there for sickle cell patients and their families, and our legislation will make it more accessible.”

Accessibility is a major concern for KMD Advocacy Center. Individuals with sickle cell often need extra accommodation as they navigate the complications that come with the disease. They frequently need to miss school or work, may not have access to care providers with experience treating sickle cell and, while curative therapies are available, they cost upwards of $1 million, making them out of reach for many with the disease. For the center, that means supporting efforts that would lower costs for patients as well as provide programs that are both entertaining and educational to make the information as accessible as possible.

One of the challenges Davis and KMD Advocacy Center face is overcoming common misconceptions about sickle cell. Davis believes one of the reasons the illness hasn’t gotten the same attention as others is that it was labeled as a disease that only impacts the Black community. But the reality is very different. While in the U.S. it primarily impacts people of African descent, high instances of sickle cell are present in India, southern Europe, the Mediterranean and Arab communities as well.

Because of the nature of the disease, it can affect different organs, and patients will often need to see as many as 13 different specialists to treat the illness. Ensuring that everyone from ER care providers to psychologists working with patients to friends and family understand what sickle cell is and who it effects is vital.

This work was why Davis was honored at January’s Lenawee County Martin Luther King Jr. Dinner. Her son John — who graduated from Adrian High School in 2010 — was posthumously recognized in 2022 with a lifetime achievement award. It made this year’s event, which donated funds to KMD Advocacy Center, a special one for Davis.

“It’s encouraging and it really touches my heart and my family,” she said. “It’s kind of bittersweet, in a way. You wish they were still here but at the same time just grateful for the community recognizing the importance, keeping their legacy alive, as well as doing what they can to help meet our goal of increasing the social and economic investment for achieving equitable care for individuals and families living with sickle cell.”

As the advocacy center continues into the future, Davis is optimistic that, with increased education and funding, things will be better for those living with sickle cell.

“I want to make sure people think about sickle cell with their heart,” she said. “I want them to think about what they would want for their own children and, as we move forward, what they could do to help. That’s what we want to see.”