ADRIAN — Experts on water quality, agriculture and the environment gathered at Adrian College’s Adrian Tobias Center on December 12 to discuss efforts to manage toxic algal blooms at the state’s first State of the Western Lake Erie Basin Conference.

Although algal blooms present concerns in each of the Great Lakes, Lake Erie’s shallow depth, warm surface temperatures and proximity to agricultural land made it particularly susceptible to algal blooms, according to the Great Lakes Integrated Sciences and Assessment program.

While the U.S. and Canada agreed to take action on the issue in 1972, algal blooms have once again become common, with 2011 and 2015 marking the largest harmful algal blooms on record in Lake Erie, with severe algal blooms also recorded in 2017 and 2019.

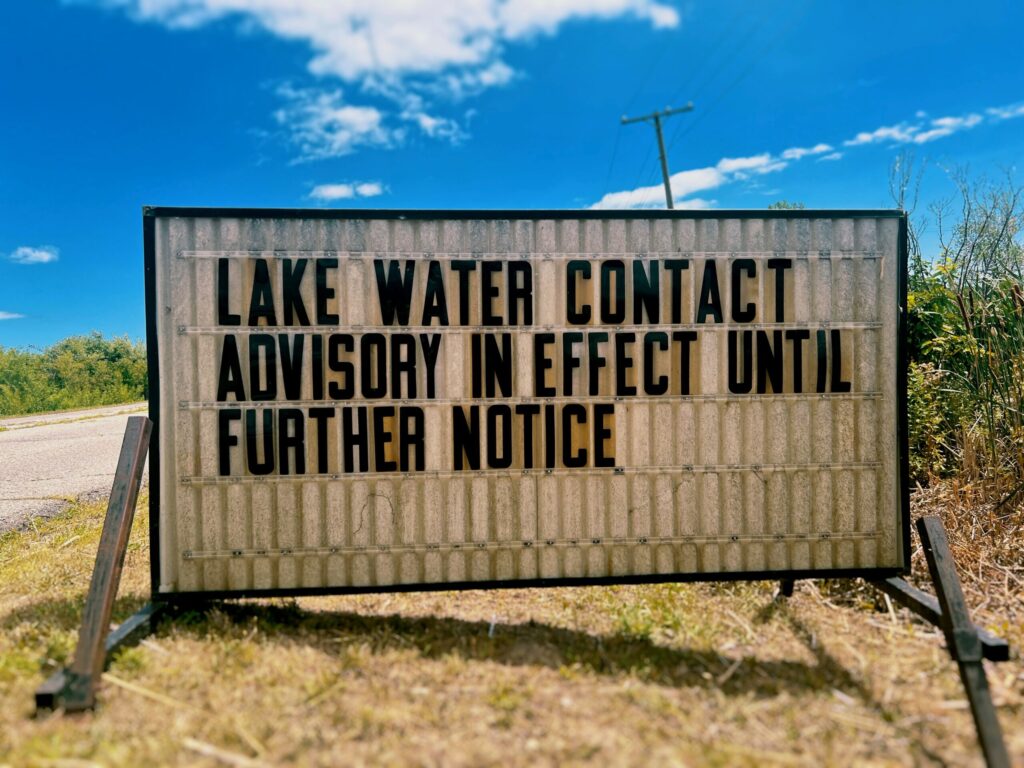

Some types of harmful algal blooms can produce liver toxins, neurotoxins and skin irritants. Harmful algal blooms can also lead to “dead zones” where algae consumes oxygen as it dies and decomposes, creating threats for aquatic animals. They can create other issues for aquatic life by blocking out sunlight and clogging fish gills.

According to Michigan United Conservation Clubs, harmful algal blooms have also contributed to $2.4 to $5.9 million in lost revenue for the Michigan portion of Lake Erie.

In 2015, the governors of Michigan and Ohio and the premier of Ontario signed on to an agreement to reduce the total load of phosphorus entering Lake Erie 40% by 2025, with an interim goal of 20% by 2020.

Phosphorus is considered a limiting nutrient in aquatic environments, controlling the rate at which aquatic plants and algae grow. However, if too much phosphorus is introduced into an environment through poor agricultural practices, urban runoff, septic leakage or sewer discharge, it can lead to harmful algal blooms.

While the state has successfully met the 20% reduction target, it still has work to do in order to meet its target of reducing nutrient source pollution by 40%.

Michelle Selzer, Western Lake Erie Basin strategist for the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development (MDARD), said the state has met its reduction target for point sources — or singular, identified sources — which has helped it meet the 20% reduction goal.

However, actual and projected reductions show the state is not meeting its goals for nonpoint source — or pollution that does not originate from a single, identifiable source — meaning the state will not reach its 2025 goal, Selzer said.

Michigan has focused its efforts on the Detroit River for point source reduction and on the River Raisin watershed and the St. Joseph River watershed.

With agriculture acting as one of the main sources of nonpoint source pollution, MDARD Director Tim Boring said there was work to be done.

“Agriculture’s got a lot of work to do. And the fact that we’re just not anywhere close to the trajectory that we need in this area. I think it speaks to the complexity of it. But it speaks to the fact that we can’t keep doing what we’ve been doing expecting different results,” Boring said. “It’s going to take a lot of work in different areas to get results in the way that all of us are committed to achieving.”

Boring identified a need for continued investment in monitoring to track where phosphorus may be coming from. The department is also in need of more research, he said.

“We simply don’t have all the necessary tools at our disposal to really nail down the problem and get into the weeds on how we’re specifically supposed to address these issues,” Boring said.

The state has already begun taking steps, including hiring water quality specialists and a chief scientist at the department, who will likely work with climate resiliency, water quality and emerging contaminants, Boring said.

“We’ve got to make scientific expertise a more fundamental part of what we’re doing at the department,” Boring said. “We are a science-based industry. We need to have science more at the heart of how we’re doing a lot of programmatic and policy development.”

The department is also investing $15 million into soil health and regenerative agriculture as part of its last budget.

“All of this comes down to changing management practices. … That’s where the soil health piece comes in, in a lot of ways,” Boring said.

This change in management will also lead to harder discussions on what management looks like in agricultural fields today, Boring said.

The department also has a lot to do when looking at current fertilizer management practices, Boring said.

“All too often we’re still applying fertilizer at rates that are in excess of fertilizer recommendations. We don’t spend enough time talking about rate, placement, timing. We’re not doing enough work on ensuring that we’re not applying fertilizers ahead of high intensity rainfall events,” Boring said.

Nitrogen and phosphorus are found in animal manure and chemical fertilizers, and can contribute to excess nutrients in waterways.

“There’s going to have to be discussions about how we continue to move away from waste disposal mindsets to more of a crop fertility based approach,” Boring said.

“We have a manure location problem, not a manure quantity problem. … The problem is we just are putting too much manure in too few places today,” Boring said.

Additionally, the state will struggle to make progress on nutrient reduction if it strictly treats it as a water quality issue, Boring said, encouraging a look at the social and economic factors that go into managing farms.

“The way you build farms today is you simplify management, you mitigate risk,” Boring said.

“We’re basically asking farmers to adopt suites of practices that the market is sending them signals to grow in exactly the opposite way. Right? These two things aren’t compatible with one another and the way that we’re building farms today,” Boring said.

It’s not the case that farmers don’t understand conservation; there needs to be economic incentives and signals for farmers to do things in different ways, Boring said.

The framing around environmental discussions in agriculture is important, Boring said, noting that these discussions often become ones about environmental outcomes versus economic indicators for farms.

“We’ve got to make this a broader discussion about who is winning agriculture. And regardless of if we’re worried about environmental outcomes if we have stakes and economic success. There’s a lot of shared values here that we’re missing out on this agricultural system today,” Boring said.

“I think there becomes a message here too as we look around our agricultural systems, like, is this what success looks like? Is this what winning looks like? Like, do you want to have to grow your farm by simply adding more acres and adding more cows to the detriment of your neighbor. Because at some point, like, we can’t all be farmers anymore if everybody has to have more and more land,” Boring said.

This discussion has to center the way residents are building the state, and what is the collective best interest of the state, Boring said.

If the state is making more concerted investments in how land is managed, giving growers clear economic incentives to achieve environmental outcomes, and residents are making more money as a result, there will be more jobs in rural areas, the health of citizens will be higher as well as the general quality of life, Boring said.

“That’s how we tackle these kinds of issues,” he said.

In addition to efforts from Boring and MDARD, representatives from other state agencies detailed their plans to reduce phosphorus loading into the Western Lake Erie Basin.

The Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy (EGLE) will be increasing its focus from monitoring four wastewater treatment facilities in the basin to 25. It will also continue monitoring watersheds for nonpoint source pollution.

EGLE will also look to expand its relationships with the Michigan State University Institute for Water Research, the Alliance for the Great Lakes and Limnotech, a water and environmental resource engineering consulting firm.

The Department of Natural Resources (DNR) will be examining its properties and practices in the Lake Erie basin to ensure they’re not contributing to the issue of nutrient pollution. It also has about $14 million in funds to use for wetland restoration, with the department seeking to invest $4 million into communities or private land to help restore wetlands within the basin, Senior Executive Assistant Director Tammy Newcomb said.

The DNR is looking to find a site where the flow comes together to create wetland to aid in nutrient reduction. The DNR is targeting the Upper Maumee or River Raisin watersheds, with hopes to move that project forward quickly, Newcomb said.

Seltzer also noted some of MDARD’s additional efforts, including a partnership with the Alliance for the Great Lakes to determine the costs needed to reach the 40% nutrient reduction goal.

The state is also working on updates to its domestic action plan, which acts as a guiding document for promoting the health of Lake Erie.

This story is from Michigan Advance, a nonprofit newsroom covering politics and policy across the state. It is republished here under a Creative Commons license.