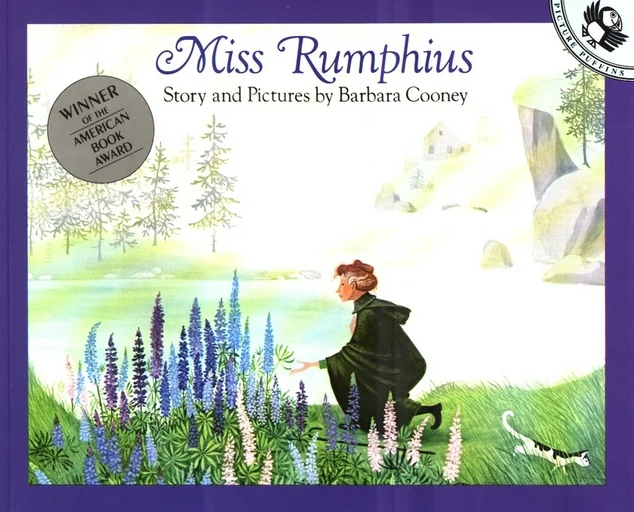

ADRIAN — In 1982, a children’s author named Barbara Rooney published a picture book. It was about an old woman named Miss Rumphius who, after traveling the world, retired to a house by the sea and devoted herself to spreading lupine seeds wherever she went — following a childhood admonition from her grandfather that “you must do something to make the world more beautiful.”

Miss Rumphius was based on a real person: Hilda Hamlin, an immigrant from England who really did have a cottage by the sea and really did sow the blue-purple flowers all over coastal Maine.

But there was much more to Hilda’s life — as her granddaughter, Jennifer Hamlin Church, discovered through over a thousand letters and dozens of diaries.

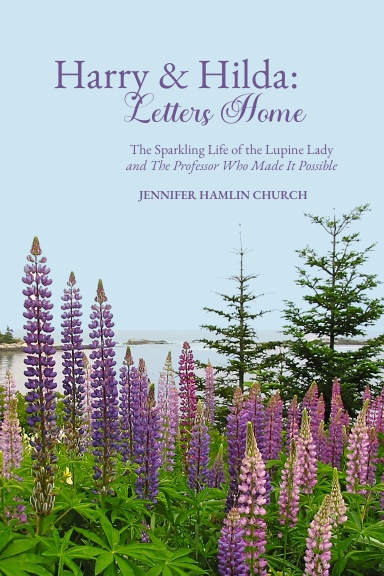

Church, a Petersburg resident who is retired as associate vice president for advancement at Siena Heights University, has documented the lives of Hilda Hamlin and her uncle, Harry Norman Gardiner, in a new book, “Harry and Hilda: Letters Home.”

The book chronicles 130 years of history on both sides of the Atlantic, through the eyes of two immigrants who arrived in America 30 years apart.

Harry Gardiner set sail for the United States in 1874.

“He came to America because he was searching for a place where a poor boy who was willing to work could get an education,” Church said.

He had written to the Congregationalist author and social reformer Henry Ward Beecher, who recommended enrolling Amherst College. Harry put himself through school by working a variety of odd jobs — teaching Sunday school, doing laundry, lighting the fire in professors’ offices every morning — and graduated with honors, eventually becoming a professor at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, and a founder of the American Philosophical Association.

His niece, Hilda Blanche Edwards, immigrated 30 years after he did.

“She came to America in 1904 because she was a difficult child, and her mother, Harry’s sister, was at her wits’ end with the oldest of her soon-to-be eight children,” Church said.

Most of the book is spent on Hilda’s life: her travels, her friends, the many influential writers, artists and thinkers with whom she crossed paths. It has been a 10-year voyage of discovery for Church, reading thousands of pages of correspondence and private thoughts, taking meticulous notes and piecing together the lives of both her grandmother and a great-granduncle she never knew.

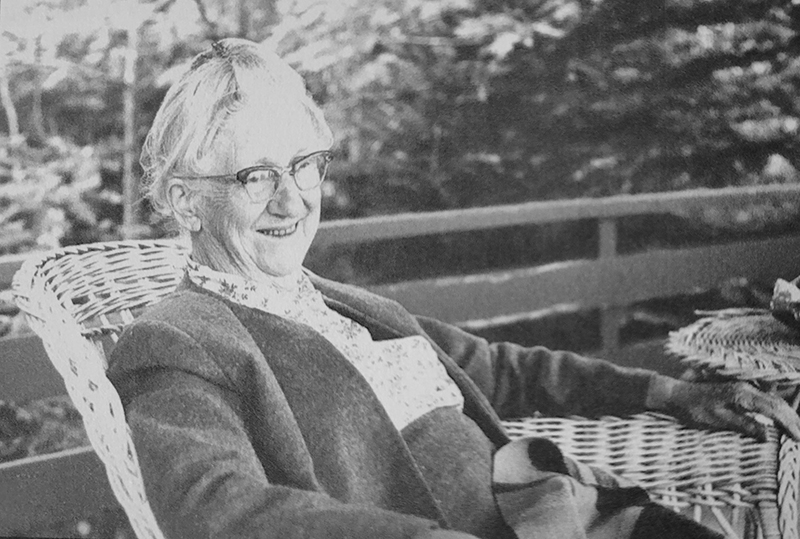

“I always found her fascinating,” Church recalled of the woman who spoke with an English accent her entire life, despite having come to America at 15. “She’d lived this exotic life. She lived in New York in the 1920s, moved to Paris and lived there in the 1920s, knew all these famous people.”

Hilda was exacting, at times excessively critical — “Jennifer, retreat thy waistline!” Church recalls hearing when she was young if her grandmother didn’t think she looked slim enough. She was a strict grammarian who would not hesitate to correct you if you made the mistake of using the wrong word. When she visited England, everything in America was better; at home in America the reverse was true.

She was also a born artist, with an eye for color and detail and a knack for finding the beauty in everything. Even a piece of driftwood that she picked up along the Maine coast could become an offbeat piece of art. “She could take bits of nothing and make it gorgeous or make it funny,” Church recalled. She would bring interesting gifts when she visited her grandchildren — nothing she bought in a store, but always something unique, perhaps an exotic item that one of her many well-traveled friends had brought her from overseas. And she appreciated a good story.

“I loved her,” Church said. “Not everyone was as fond.”

“She was just different. She wasn’t like everyone else’s grandmother.”

Hilda’s habit of collecting interesting people goes back to the long trip over the ocean that brought her to America. Not long after tearfully saying goodbye to her father at Liverpool, she was befriended by a family who turned out to be relatives of the great actor Joseph Jefferson. His grandchildren whom Hilda met on the ship would go on to become famous in their own right, including Eleanor Farjeon, a celebrated children’s author and poet who wrote the hymn “Morning Has Broken.”

“It’s just an example of the kind of Forrest Gump life that both Harry and Hilda lived,” Church said of that chance meeting.

A divorced woman at a time when divorce was rare, Hilda was strongly independent. She would visit family and enjoy their company, but she was always glad to get back to her own home and her own life. Her letters and diaries read like a “who’s who” of the literary and artistic world, dotted with friends like the sculptor Alexander Calder and the influential food writer Clementine Paddleford.

“Doing research with letters and diaries is both thrilling and deadly boring,” Church said.

There is a lot to slog through — but, she said, “if you’re careful and if you’re lucky, you do solve mysteries.”

One such mystery was the identity of Hilda’s midlife romance, who she never mentioned by name but who turned out to be the writer and painter Victor O. Freeburg.

Hilda was well into adulthood when she began the habit that would bring her to fame. She had learned to love flowers as a child in England, and during the Great Depression, she wrote to her brothers asking them to send her some seeds.

She spread them around the cottage on Christmas Cove that she had inherited from her uncle, she scattered them by the roadside, she even tossed them into other people’s gardens. She did this for many years without receiving much notice, but in 1971 she was profiled in an issue of Yankee magazine, and summertime found her deluged with visitors who wanted to meet the “Lupine Lady.” There were so many that, exasperated, she took to calling them her “Damn Yankees.”

With the publication of “Miss Rumphius,” her reputation only grew. On her 100th birthday, a reporter visited her in the nursing home and asked how she decided where to sow her lupine seeds. She couldn’t remember at first, then she smiled and said: “I used to throw them in the gardens of people who didn’t have any.”

Hilda lived several more years after the book’s publication and died in 1989, two weeks before her 101st birthday.

“After her death, more and more she was remembered for that one thing — that she was the real-life Lupine Lady,” Church said.

“The point of my book is that she was so much more than that, and that she had been a fascinating and accomplished person.”

“Harry & Hilda: Letters Home — The Sparkling Life of the Lupine Lady and the Professor Who Made it Possible” can be ordered on lulu.com.